By Natalie

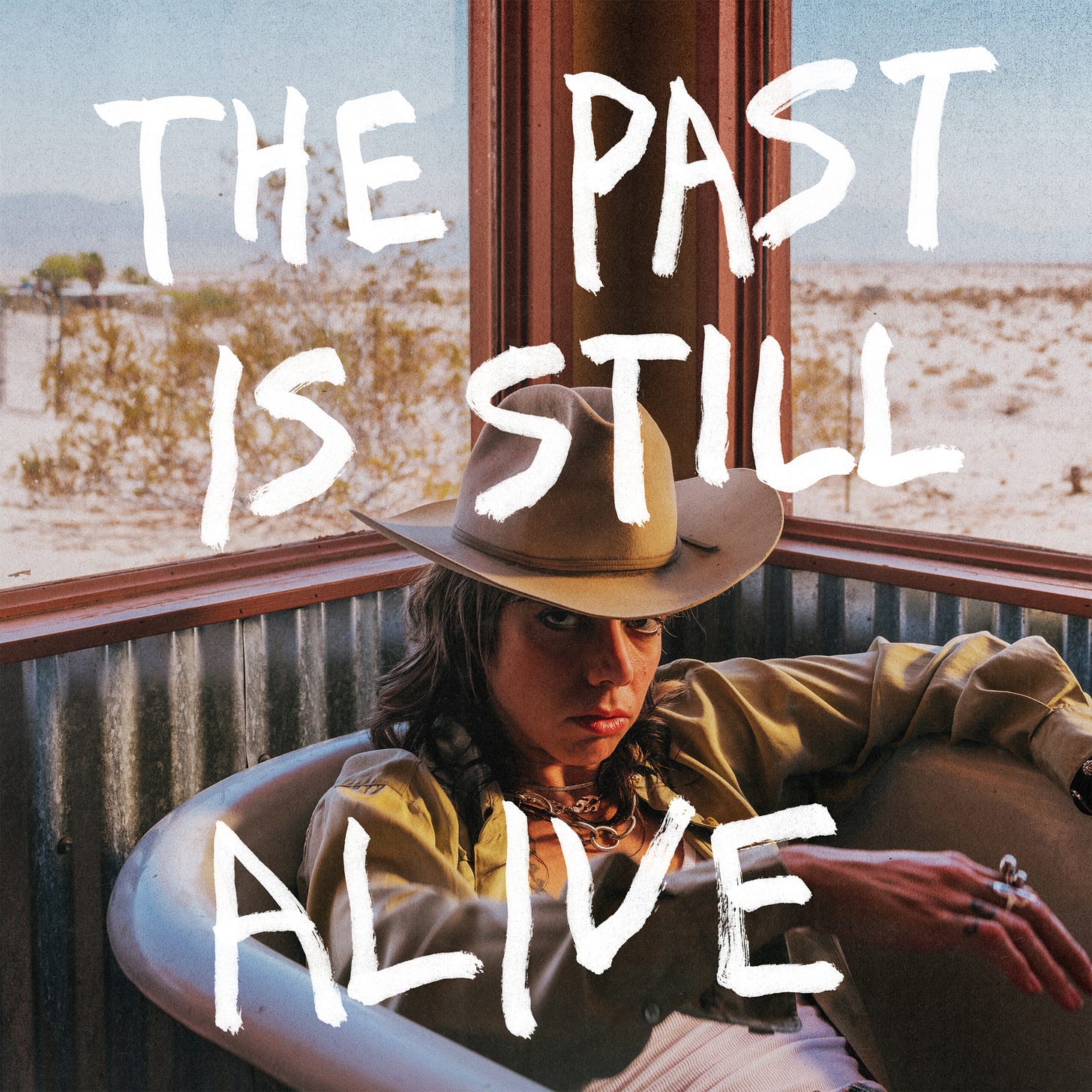

The Past Is Still Alive is undoubtedly one of the best albums of the year, brought to us by the persistently original, deeply thoughtful and as I now know a little in person, endlessly generous Alynda Segarra and their musical work as Hurray for the Riff Raff. It's one that rewards repeat listens, full of vivid stories told with clarity and deep feeling.

I was lucky enough to speak with Alynda at Americanafest a few weeks ago, a conversation I was extremely intimidated by but that Alynda could not have made easier or more fun (even though we waded through some heavy topics). Their curiosity, ambition and humility, I hope, are evident in the edited, condensed version of it presented below; if you're interested in hearing more musings from Alynda, I heartily recommend their new newsletter .

"It's a practice to resist," as they put it, explaining the Bikini Kill-inspired title. "To resist psychic death is to resist losing your inspiration and your love and your passion for life, because there's so much that wants to numb us and wants to get rid of these little romantics and dreamers that live inside of us." Yes, a thousand times yes! For your reading and listening pleasure:

What was the initial impetus for the album? How did it change from when you started writing and through the recording process?

I started writing this record when we were still in lockdown. I was in New Orleans, and in the process of making Life On Earth — me and [producer] Brad Cook were meeting in Durham, I was driving there because I didn't want to fly, we were taking COVID-19 tests...it was this really intense time of not seeing a lot of people and being really separated from the world. As we were finishing up that record, I wrote "Snake Plant"; something opened up in my mind about memory, and linear time, and my difficulty living with linear time. We were all in this period of wondering if the world that we knew and the life that we knew was over, and it really made me take stock and think about everything I had lived already. It made me think about communities I've been a part of, people and movements that I've been a part of and also just witnessed. I started to feel this urge to be a documentarian: to use songwriting as a way to document these people that I loved and also kind of keep them. I felt like time was going like sand through my fingers, and so it was my way of holding these moments and these people close to me.

That was the original idea. I started writing these songs while on the road, and then my father passed away very suddenly. He was a musician and a really big part of my life and my music. I was set to go into the studio a month later, and it was this really traumatic and...mythological moment for me. It was like, "This is the vessel that I could put my grief into, my love into." I was so grateful to have this record to process. At first it felt like I was writing the album in this really academic, a little bit separated way, and then suddenly it became way more raw, way more stripped down and vulnerable.

You've talked a lot about grief, obviously on the record, and then kind of around the record. It's made me think so much more broadly about what grief means — the way you're talking about grieving your father, obviously, but then also kind of grieving your past selves a little bit by honoring them. We often think of grief as something to…get past, and it feels to me, the way you're talking about it, it's almost like we need to embrace it as a way to honor and love.

Obviously it is such a big loss for me. I remember feeling very scared. I felt like I was going up a roller coaster and I was about to go down, and I didn't know how long I would fall for. I realized I felt like grief was a punishment, and it took me a little bit of time to realize that it's just another expression of love. I was lucky to have people to fall back on and to have this record to find a way to live with it, in a way — to walk beside it. This record was like the chariot to take me on that road, because without it, I think I would have been really lost.

We don't really have a lot of long-term ritual in our culture, and it's so unfortunate, because grief is the most human experience that we're going to have. It makes you more human, it makes you more loving, and it also brings out the worst in you. It stirs up so much that you're trying to contain as you're like walking around, trying to be normal, going to coffee shops, going to work. I'm lucky enough to be a crazy artist, so I needed to really allow all this stirring up — but I have this womb of the recording studio to work out that stuff. Luckily me and Brad had already cemented a really strong working relationship working on Life On Earth, so I was able to go in there and just kind of unapologetically be like, "This is the state I'm in, so this is what this record is about now — or at least it's our guiding light."

The album has a lot of vignettes from more specific parts of your past — specifically your time riding trains around the country — that might be sort of removed from a lot of your listeners' lives. You've talked a little bit about how you'd been reluctant to share some of those stories because that community feels both really special to you and kind of fragile in a way, or precarious. How did you come to a place where you felt, "Here's a way I can tell these stories, but also not expose them, not make it voyeuristic"?

It just took some time for me to get a little wiser. Now I find, with people from this past life of mine — people that I lived with on the street or played with on the street, or rode freight trains with or whatever — their response is more like, "Wow, thank you for writing this down so that it exists in the history books of some sort." Now it's become much more of a "Well, we need to write down these people's names because we don't have them anymore, or this moment on this certain campsite." We might lose it. It isn't digitized, it isn't, like, on YouTube.

Also when I first started getting press for Small Town Heroes — a record that is 10 years old now, which is really wild — I felt like I had a lot to prove, because I really wanted to be known as a songwriter. I want it to be known as somebody who is obsessed with craft and loves folk music. So I just felt like I had some work to do. I still do, of course, but I feel a little bit more like, "Okay, I've made three records now that I really love, and now I can talk about my life, and be a little bit more vulnerable or raw."

The album, at least for me, is another entry in the canon of artistic works showing how close we all are to that world "outside"; a world of people choosing (or not) to live beyond our tenuous, imagined norms.

That's the work that just called to me ever since I was young. That was the poetry that I loved, that was the music I loved growing up in New York. When I found Woody Guthrie, it completely blew my mind. But I felt like Woody Guthrie was talking about some of the people that Lou Reed was talking about. It felt like, "Well, they would hang out at the same party, and hang with the same people in the park." This idea of folk music and rock and roll and outsider art — it made sense to me. This is just my world. With this record, I learned a lot about my language. It felt so freeing to be like, "Oh, I can just use the words that mean something to me." Kind of writing out these keywords about riding trains, or about busking or about being on the street. We all have our own languages and keywords.

What was the process of making music videos for this album like?

We were playing around with a lot of archetypes and characters. I've been obsessed with My Own Private Idaho, it's like a sickness. I just think about that film all the time. Think about River Phoenix, think about Keanu. River Phoenix just embodied this James Dean archetype, this sad boy, dusty American character that's like out wandering, has a poet's soul, is wearing work clothes even though it's like, you don't work... That was the type of character that I was drawn to when I first started writing poetry and when I ran away, and I just felt like, "How do I just allow myself to kind of fill these shoes of this imagery and this romanticism?"

As somebody who's kind of shy, and learning as we all are to accept the way we look and accept ourselves...it was really important for me to see myself in these videos and to see something that existed in my mind. I felt like I was freed of some of the trappings of "You have to look like this. You have to dress like this" that we're all told about gender, about everything. Seeing these videos back, it was a really vulnerable experience with the director, Jeff [Perlman] — it was like the world of the album was coming to life. It wasn't a character — for this side of me, this persona that lives within me to come out felt really natural and empowering.

So often we think about that '50s countercultural iconography as so cis-male and white — it's so cool to want to take that influence and imagine a more inclusive vision, one that's more accurate by virtue of being more inclusive.

It's just the imagery that I like. So instead of throwing it away, it's like, what if I could be that? A lot of, "What if?", a lot of playing, a lot of taking chances and also a level of vulnerability. When you're playing around with iconography like this, you expose yourself to being made fun of…people are so mean! Overall it's been a really beautiful experience. And also, it made me a little bit tougher — like, I don't care. This whole record, every part of the process — after the writing, after recording it, making the art that goes with the songs — it's all been a really transformative experience for me of just feeling more comfortable in my skin.

It also brings up a favored country/Americana trope: the idea of an outlaw. When you talk about living "outside," you're talking literally, obviously, but I feel like on a figurative level too, there's so much there — trying to be outside of surveillance. I feel like it's kind of a throughline of the album, too, the idea of escaping in a way, or going undetected...an interesting different conception of the outlaw.

I think of the word "drifter," right? I’ve felt like that since I was born. Even before I started traveling, I didn't feel like I belonged in my family, I didn't feel like I belonged in my home, and I was also being thrown around to many different homes. My happiest moments were riding the subway — just being like, I will ride this subway car for two hours just to go to the wonderland of the Lower East Side. It was about like…entering portals. The time that I grew up in was also like the beginning of a heightening, or more of a public acknowledgement of surveillance. I was a freshman during September 11 in New York, it was my first week of school. When people are like, what drives you to write songs that are politically meaningful? It's like...hello! This is just the backdrop of what we've all been living in.

I was living in a counterculture and what's really funny is that we were all trying to avoid being documented. That was the goal, to go unremembered. With time and with creating a career and needing to be documented and also it becoming just so much more a part of our lives, I’m learning how to make art with that, learning how to reckon with it, and also now learning how to go back and scour through all these moments where we told everybody, "Put down your camera!"

You were mentioning "keywords" for the album, and one that I felt like popped up a number of times for you was war, actually. You characterizing yourself as a "war correspondent" on "The World Is Dangerous" —

That was actually somebody else! I'm the "wandering loser." [laughs]

Whoops! OK, well I was developing this whole theory about how you were writing these songs as honest dispatches from the "war on the people" ["Snake Plant"]...

No, it was specifically about somebody very close to me who was doing really important humanitarian work overseas. There was a lot of tension in all these relationships on this record of me being like, “What am I doing? Like, is what I'm doing anything?” But then also finding a place where our attentions and our crafts met in a really beautiful way. Also, though, to be so aware that there's war brewing all over. I think about that with "Colossus" as well, creating songs that feel like bomb shelters, that feel like pillow forts, places that for three minutes you can be in a protected space and still acknowledge what's happening outside — but to be safe, just for a moment.

It all made me think of a thing Lizzie No said when we spoke with her not long ago about how she's just trying to "advance the cause of species survival." And I was like, Whoa. That's such a cool way to think about creating a future when it seems like there isn't one.

I've been thinking a lot about how artists right now, especially musicians, are in this really tough place where sometimes or often, it feels like, “Is what I'm doing important at all? Like, does it have any value?” But the work that we do, without being overly romantic about it, it is a lot of envisioning, a lot of imagining. It's important for society to have imaginers and dreamers, and also to for us to witness other people's dreams and visions for the future that for whatever reason, maybe they don't have the time to express. Someone like me gets to witness it, hear it, and be like, "That's so important, other people need to hear this." I'm really trying to step into that role more. I love when artists are able to be ambitious in the way that they talk about their work. It doesn't have to be egotistical, it's the opposite. It's serving a purpose, and it's an honor to do it, and it's difficult work and it's also wonderful. So I'm really trying to step into those shoes too.

One thing you mentioned in a different conversation about the song "Buffalo" centered on the idea of relaxing into your work — pushing through the feeling that maybe you weren't doing enough, and just kind of letting it happen. How was that a change, and how did it feel in the moment?

Ambition sometimes also can really hinder me. I can write a song like "Pa'lante" on The Navigator, which took like, three years. It gets a little bit like, "Well, this is what I should be doing, writing ANTHEMS!!" This pressure can also make it...that song was supposed to be like that. This time, though, I tried to allow, again, for the language to come. A lot of the lyrics in "Buffalo" are just memories of exactly where I was and what it looked like and what was happening. We were in a little chapel that had children's shoes on the ceiling. Also this idea in "Buffalo" about patience and love, and really investing time and allowing a love to grow and how difficult that is in our world — like, somebody else better might be around the corner! So "Buffalo" meant a lot to me in this idea of just slowing down a little bit; asking, "Does it have to be an anthem? Does this have to be better? Perfect?" It could just be, and be real to my experience.

It feels very mantra-esque. The first thing I wrote was the chorus; sometimes you get a part of the song, and then you're like, "What are you trying to tell me?" It's a lot of, like, medium work, you know? Talking to the ghost, like "What are we trying to say? Where are we going?" And then you just slowly find your way.

In this album, it feels like you so successfully managed to marry the lyrics that obviously you spent a lot of time on with production that really centers those lyrics. The recordings started just with you and your guitar, right?

That was really important to the process. With Life On Earth, I really needed to break out of my own head, and we needed to explore and to write in a different way and play different instruments, and it was so fun and so good for me. But when these songs started to emerge, it was pretty obvious immediately that they didn't need that, that they needed me and my guitar. So we would record that and then add around it. It just needed the perfect little touches. That process was also really good for me to just be raw with my vocal takes. Just like, "We're going to do three or four, and then we're not going to think about it." Because I didn't want to be perfect, I didn't want to nitpick. Being in grief brain, I had a lot more, like, "I don't know, you tell me when you think you hear it." Because I didn't have the energy to even nitpick myself.

The Past Is Still Alive; I've read things where people seem to be reading it as a metaphor or as an impossible dream or something, and it's so real.

These people that we've lost are still with us. And the history of the places we live and go to are still with us. I mean, I'm going to go to the Ryman later (!). These characters, these ghosts, these experiences, they're all still here. The title came to me, and at first, even for me, I was just like “What does that mean?” Again, with the medium thing of just being like, "Tell me what it means!" And then slowly, I see it everywhere.

To close out, I just wanted to ask a little about, as you've characterized it before, being pigeonholed as a "liberal hope" — sort of carrying yourself through all these spaces where there are people projecting things onto you and there are so many expectations of you.

It goes back to why for a while, I was just more guarded about this world that I come from, because I didn't want it to become a Disney version of it. It's beautiful and it's horrifying, it's everything. I think we lose a lot of those complexities when we talk about certain artists and their work. Especially after Navigator, a lot of people would ask me in interviews, "How do you stay so hopeful?" and I'd just be like, "What?" I mean I'm trying, you know, and also I'm learning a lot about hope, and about belief and how it is deeper. It's not always pretty, and it's not saying everything's okay or that everything's gonna be okay. I just really want my work to say more of, "Well, this is the reality."

I felt a groundedness, a rootedness in this record of like, this is where we're at. This is what we're up against. This is what we're dealing with. We're dealing with a lot of chaos, a lot of division, a lot of fear-mongering and violence around the world. This is just where we're at, so let's embody our purposes. Let's really embody how we were born in this particular time. It's so important to recognize that we were supposed to be here, right now. So I'm really just trying to use this band and the writing to say, "Yes, there's a war on the people and everybody should be carrying Narcan," and to also say, "I am always dreaming of the future. I do think that there's a beautiful future that's possible.” We have to envision it, and it's not going to be easy. To give up on that hope just seems like, well, then what's the point? It's just our work to do.

Thanks for opening a portal into the bomb shelter of Alynda’s mind! Loved this interview + this album so fiercely 💙

In case you hadn't run into it, Maria Jane Smith's "Adrian" is an odd outlier that sort of *feels* like a country song, even though it's by a Swedish artist and also kind of veers towards dream pop: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0OBo_rqBVqA