On 'Soul-Folk', with author Ashawnta Jackson

These days, the too-often ignored history of Black artists making country music looks like positively well-trodden territory compared to the story of Black artists and folk. Enter Ashawnta Jackson's Soul-Folk, a quick guide released last year to a whole subgenre that stretches far beyond even the brilliant artists you might instantly think of: Harry Belafonte, Odetta, Nina Simone, Richie Havens… Jackson traces Black artists' core importance to the history of folk while also exploring a '70s wave of artists who used that heritage as a jumping off point to make really wonderful, creative, experimental and liberating music.

Jackson is now working on a book about Black-owned record labels — but she still took a few minutes to chat with us about Soul-Folk.

Natalie: Soul-Folk accomplishes a lot: shares a lot of little-chronicled history, traces a new narrative almost between genres, offers plenty of overlooked artists to explore. I think by articulating this genre, you've made a really effective argument for expanding and reimagining the canon. What was important to you as you put this together?

Ashawnta: I view my work as telling these stories that don't always get told. Especially when you look at Black communities and you see how other people have tried to tell our stories, it feels flat sometimes. But we're fortunate that a lot of people are still here to tell their own stories. For Soul-Folk, I was able to talk to one of the artists, and he really thought that his music was going to be lost. Now not only is it not lost, but people are listening to it and appreciating it — and it matters. What he did mattered. While I do like to kind of take a step back and say, "Oh, I'm the storyteller," I also feel so privileged that I get to tell those stories, and that people trust me with them. Especially with the way things are right now, telling your story is sometimes the most important thing you can do — to leave a record that you were here.

When I started writing the book, I had this idea in mind of what kind of story I wanted to tell. But the more I kept digging in, it kept going further back, and further back, and further back. And then I realized like, okay, this story has been told through oral history and through the music for all these generations — but they just keep leaving us out! It feels pretty similar to what I'm working on now, when people are like, "Oh, Black-owned record labels, like Motown." Yes, like Motown, but also way, way, way before Motown.

NW: What surprised you most as you were researching and writing? As you're saying, so much of the story was there in pieces, but not really presented together, coherently.

AJ: When I had initially pitched the book, I did have this idea of what this genre was. And the thing that most surprised me as I was writing it was that…it's not really a genre. The more I started learning and listening, the more I realized that while it is helpful to give it a name, it's also so confining to put the music into that small box. The more I was writing, the less I felt that it was actually a genre, which is kind of…antithetical to the whole project.

NW: But you know and I know that genre isn't real. That's the caveat I'm constantly giving here at DRTI — like, we're a country music newsletter but one that acknowledges that genre is not real.

AJ: That's another thing — a common thread for many of the artists I wrote about is that that they just didn't want to be put into a genre. They were like, "I just want to express myself through my music, and this is how it sounds." There's this kind of tension about giving it a name when the artists were so resistant to being defined. That resistance is also one thing that made that genre hard to market. As I was writing, I was just trying to find that space in between all of that — between wanting to be on the outside, and knowing that people need names and categories to understand things. It was difficult to thread that needle and not just throw my hands up and say, "Well, but it doesn't exist. Here's some music to listen to, it doesn't exist."

NW: You did a pretty graceful job of articulating that in the book, too. It seems like especially in this specific case, you're right that giving it a name and creating a story is more likely to help these artists be remembered because you're lending a coherence to this arc — it's not fair that that's how it works, but I do think it makes a difference. There are so many more familiar names that pop up around the book — Harry Belafonte, Paul Robeson, Odetta, Nina Simone — how did you decide who to hone in on when there were clearly so many directions to go?

AJ: When I was working on it and I would tell people that it was about, they'd say, "Oh, Richie Havens, right?" And going in, I guess I thought, "Well, of course I'm going to talk about Richie Havens." But ultimately, I was the one that had to define the term. I wanted some of the artists to be a little bit lesser known, and because I think that the idea of soul-folk is about how it resonates with the listener as much as it is about what it sounds like, how the music resonated with me mattered. Did it make me feel like I was listening to something that was connected to jazz, to folk, to R&B, to spirituals and reaching back, and reaching back, and reaching back. I decided I could write a whole book about Nina Simone, so I did purposely exclude her — because then it would just be about Nina Simone.

I went into it with the idea of definitely who was going to be in it, and then it changed as I learned. I guess I'd like the same thing to happen for the reader — to maybe go in with an idea of what this music is, but to maybe leave with a different one. That's how I approached the epilogue, with the idea of inviting everyone to think about what this music means and how it's living past the one kind of specific moment that I really concentrate on, the '70s. To think about how we're hearing it today.

NW: I thought your observation that authenticity is not about the performer, it's about the listener — creating a context where the listener can pretend that the music is "real" — was so brilliant, and such a smart way to articulate a thing that obviously is perpetually being negotiated in country and folk, genres that are so obsessed with being perceived as authentic in some completely nebulous way. How does that idea connect with country and folk specifically to you?

AJ: Country and folk are genres that have for whatever reason, even though it's ahistorical, have decided, "This is what a country musician looks like and how they behave." We somehow all decided to play along with that for a lot of years. The ongoing resistance to accepting outsiders — and again, that's ahistorical because they aren't outsiders, they're part of the canon too. You just keep pushing them out and then blame them for not being on the inside.

Folk and country, like, that's music for and about the people — and that means all of us. We just all became very, very comfortable with the idea that this thing has to look like…this one specific thing. I think that's one reason why everyone was so excited about Cowboy Carter. And it's like, okay, it's great to be excited about that. But don't act like this is new. She's speaking to a whole tradition of things that came before her. While it was kind of cool that year to see, people be like, "Oh, black people do country music and here's a list," it's not enough. If you're just going to list names but not actually trace the music back and listen to and find those points where the exclusion started, find those people who might very well fit into the idea you have of what the music is supposed to look like and sound like…

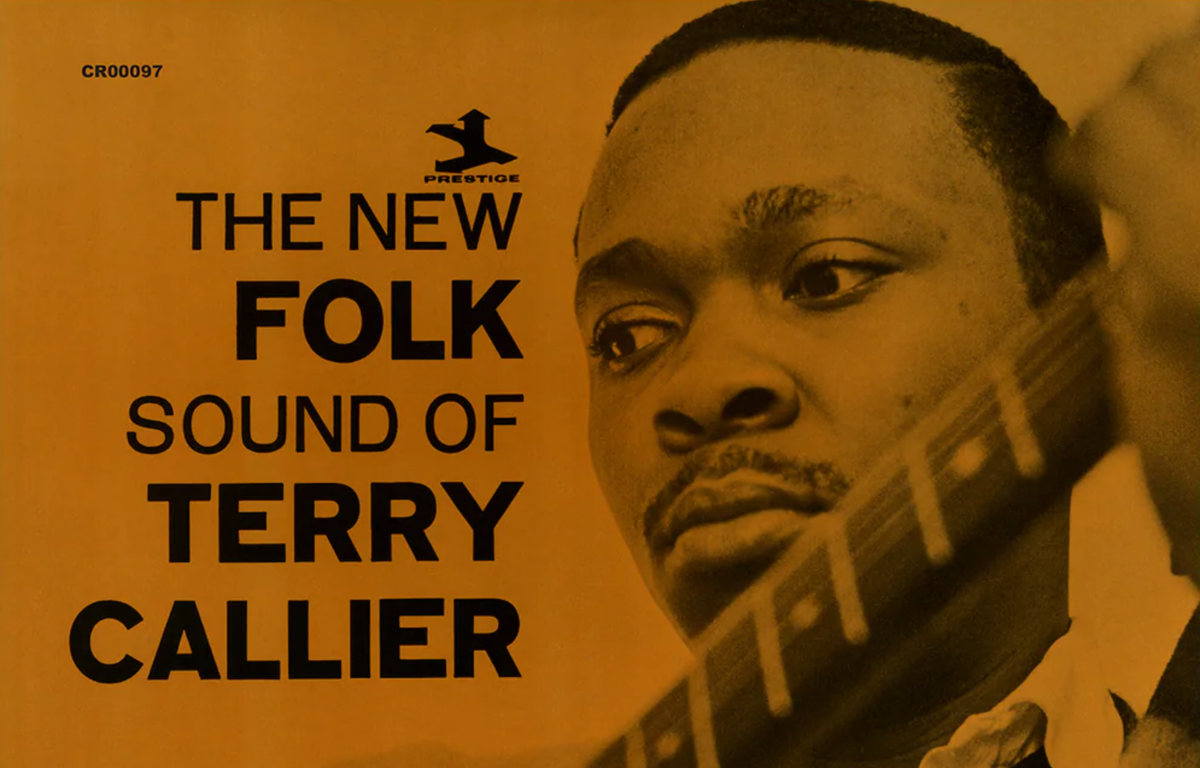

I think we've all fallen into the idea that something is authentic or not authentic or real or fake and you know, it's hard to escape that. I had to sit with it myself a lot to think about… like, Terry Callier is one of my favorite artists, and when I first listened to him, I don't know that I necessarily pinned it as folk. Like, no, this is different than folk because it's soulful and it's this and it's that. But why can't that be folk? So I was even playing into it myself while listening to music in the folk tradition, and I'm telling myself that it's not folk because he doesn't look like Bob Dylan. That's crazy! It takes a lot to break those expectations.

NW: It makes me think of the Isley Brothers album Givin' It Back, where they do a bunch of like soft rock covers and on the album art they're dressed in t-shirts and holding acoustic guitars — sort of a nod at like, this is what you like from the white guys so you should like it from us too. It's just clear that they were completely conscientious about the fact that the kind of expectations and ideas you're describing were a big part of the reason they weren't as successful as their white counterparts.

AJ: One of the people I spoke to, Cleveland Francis, he was saying that it was really hard for him to watch his white contemporaries sing about civil rights and injustice. He was like, "But it's happening to me. Why can't I sing about what's happening to me, instead of listening to other people tell me what's happening?" There's always this resistance to letting people tell their own stories. Who has the right to tell these stories? All of a sudden you know, it's Joan Baez, who I have no issue with, singing these beautiful hymns and spirituals. It's like, okay, but she's not tied into that tradition. Who gets to tell the story? She's doing a beautiful job of it, but can we let somebody else have the mic?

NW: I'm a big fan of what often gets called "soul jazz" — how do you (or don't you) see the connection between the ways "soul" is used as a modifier there and with soul-folk?

AJ: It's another one of those things where e the box for it, the name of the genre feels so limiting. Soul is so indefinable. I kept going back to Phyl Garland's book, The Sound of Soul, which I used a lot for reference. She's writing a whole book trying to define soul, and it's really hard. The thing that makes soul beautiful is that you can't really wrap your arms around it. You just kind of know it when you feel it — that's with both soul-folk and soul jazz, where it's this blend of two vital parts of soul: the spirit and, you know, the fun stuff. Saturday night, Sunday morning. You hear that it's rooted in church. You hear that it's rooted in praying grandmothers and long Sundays spent in hard church pews. But you can also hear this kind of sexiness, this kind of forbidden thing, like the thing you have to go to church to repent about.

It's this kind of intertwining of those two that I think defines that soul modifier. Soul has tension, you know. Cannonball Adderley is such a good example — when you hear those moments where it feels like the band has got to come apart at the seams, and they're in that really good space, that's soul.

NW: So many of the artists you talk about in the book don't fit neatly into any genre (hence the need for you to define one around them) in a way that white artists get praised for and, typically, Black artists are punished (by the market or otherwise) for.

AJ: That's one of the reasons that I ultimately decided that I was going to put Bill Withers in, even though he's somebody everybody knows. At the beginning of his career, there was still this question: "Where did you fit? How do we market him?" That's been so much of a problem, that it's not about like, "Who will hear this beautiful music?", as much as it is, "Who can we sell this beautiful music to?" Those are two very different approaches, selling it versus just making sure people hear it.

NW: I want to call out specifically one of the artists you include in the book, Eugene McDaniels, who released an album in 1971 called…Outlaw (!). And he's wearing a cowboy hat on the cover! Wild synergy with the "outlaw country" movement.

AJ: I think he realized right from the get go, like, "This is not going to be popular. I'm just gonna do what I want." He came from these really saccharine pop songs — that "Hundred Pounds of Clay" song is one of the worst things I've ever heard. He came out with that album after being known as a poppier dude, and then he's out there calling his album Outlaw and saying, "I'm in this weird outsider space and I like it here." Because he wrote a very popular song, he had enough money to be like "Fuck you, I do what I want." He made such weird, beautiful, interesting music. And that's the thing I really came away from this project understanding: There's so much weird, beautiful music, and because it doesn't fit existing definitions, people aren't listening to it.

Buy Ashawnta Jackson's Soul-Folk here, and check out the listening guide she made here.