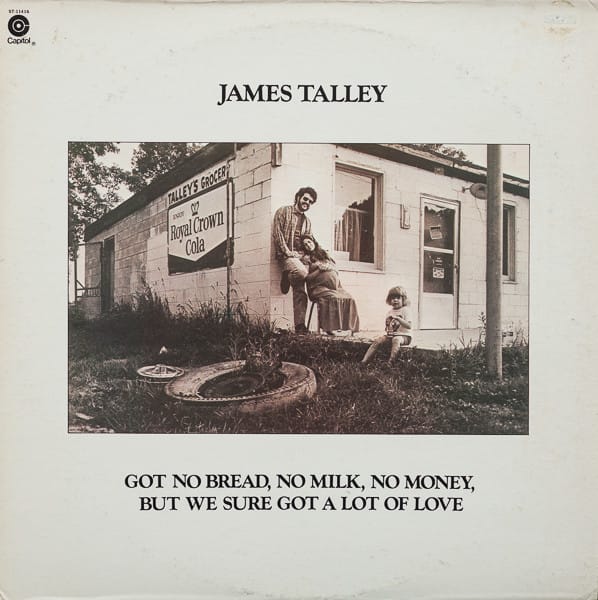

James Talley On 50 Years of 'Got No Bread, No Milk, No Money, But We Sure Got A Lot Of Love'

The veteran singer-songwriter talks with DRTI about his timeless debut, and the half-century since.

In 1975, the outlaw movement was near its critical and commercial peak, with plenty of Americans city, country and in-between drawn to the saga of Willie and Waylon and the boys. One of the year's most critically acclaimed albums, though, was made by a singer-songwriter who was even further on Nashville's fringes than those proud outsiders. James Talley, born in Oklahoma and raised in Richland, Washington and Albuquerque, New Mexico, released a stripped-down but enviably rich collection of songs he'd written about being a poor Okie in the time of Bob Wills — about his parents and family, basically — called Got No Bread, No Milk, No Money, But We Sure Got A Lot Of Love and charmed just about every national critic of the moment (cue Christgau calling it a "Western swing" album…sure).

Talley's debut wasn't necessarily political besides that it came from a working person's perspective — a tack that he's maintained for the half century since. On his second album, he recorded the now-standard "Are They Gonna Make Us Outlaws Again?", eventually recorded by none other than Hazel Dickens; you may have learned about his most recent album last year from a DRTI shout out for "Jesus Wasn't A Capitalist." His message and his thoughtful, vivid songwriting have remained constant, which is why we're so glad the 82-year-old artist elected to chat with Don't Rock The Inbox about 50 years in the business and what it was like putting that timeless record together all those years ago.

Natalie: Your first album turned 50 this year. You financed it yourself, right?

James Talley: It was actually recorded in 1973, but it didn't get released until 1975. Basically, I got free studio time for some carpentry work that I exchanged, and all the players came and played on it on spec — the idea that at some point, maybe it would be sold and they would get paid.

NW: There was so much happening in Nashville at that time. How did you sort of find your musical community there?

JT: I didn't really get to know too many people, to be honest with you. I came here and had to get a day job right away to support myself. I had worked as a welfare case worker for a year in New Mexico, and so I said, "Well, there's probably poor people in Tennessee too." So I took the welfare worker exam and I got hired as a case worker. I met my wife at the welfare department — we went together for a couple of weeks, and I asked her to marry me. She said that she would, but thought we should wait a little while. I said, "Sure, I'll wait as long as you want." So we waited another two weeks. I was married to her for 56 years. She passed this last January.

I was working regular jobs and writing songs — I would try to take my songs down to publishers and whatnot. The first project I tried to pitch was a combination of photography and music about Hispanic people in New Mexico. Cavalliere Ketchum was the photographer, and [before I moved to Nashville] I was writing songs about the people I was working with. We wanted to put together a package kind of like Walker Evans and James Agee's Let Us Now Praise Famous Men [it would eventually be released as The Road To Torreón]. That's what I was focused on when I came to Nashville, because I didn't realize that Nashville was just mining a very narrow commercial channel of music. I knew nothing about the music business, I just loved writing songs. I took these songs down to the Glaser Brothers' publishing company, and they helped me make a demo of them. I took those songs around — I played them for Billy Edd Wheeler, who at the time he was working over at United Artists Publishing. He said, "Well, this is amazing stuff, but there's nothing I can do with this in Nashville. You should record these songs yourself." I mean, I never really fit into Nashville. I loved Jimmy Rogers and Woody Guthrie and Merle Haggard and Mickey Newbury.

Talley had the chance to play his demos for John Hammond at Columbia; he liked them, and referred him to Clive Davis, who vetoed the project. Hammond then sent the demos to Jerry Wexler, who was in the midst of trying to start a country division of Atlantic Records. By this point, Talley was working for the health department as an educator.

At one point, I was down in Memphis leading a teacher in-service day. I was giving this slide presentation to all these teachers in Memphis on syphilis, showing all these ugly canker sores and all this crap — and I had this epiphany, standing there in my little tan poplin suit and neck tie and everything. I said, "You've got a degree in fine arts, what in the hell are you doing here?"

Not long after, Jerry Wexler called me and he said, "How much money do you make at the health department?" I said, "Well, I just got a raise on making $900 a month." This was in 1972. He said, "I'm going to pay you $250 a week. I want you to quit your job and write songs for me." I thought I'd gone to heaven. I wrote religiously, every day. So I had this huge backlog of songs.

NW: That was when you wrote the songs for Got No Bread, No Milk, No Money?

JT: My father died the first year that I moved to Nashville. My mother and her sister came to visit me, and I told my aunt that I found this stash of Bob Will's records down at Buckley's Record Store down on Church Street — these little Harmony reissues, just the cheapest reissues you could get. They didn't even put them in paper sleeves, just shoved the LP into the cardboard and shrink wrap. I got them because my parents grew up in Oklahoma and they used to go to Bob Wills dances. My father thought the sun rose and set on Bob Wills.

My aunt said, "Well, if you like Bob Wills, you should have heard him when he was with W. Lee O'Daniel and the Light Crust Dough Boys." And I said, "Who?" She said, "That's how Wills got his start." I thought, man, what an incredible name — that sounds like a song to me. Jan, my wife, loved to research things, and she went down to the Country Music Hall of Fame and got a bunch of information about W. Lee O'Daniel.

So I wrote that song. I don't think O'Daniel really ever played in Tulsa, but I wanted to set the song in Oklahoma, with my parents and my relatives all going up to the dance on Saturday night in Tulsa. That was the idea behind all of those songs. I said, "Hell, they don't want any of these songs about Hispanics in New Mexico, I'm just going to make a country album." Or what I thought would be a country album.

I made the album, and played it for a couple retired record executives. One of them said, "Well, that's too country. Too acoustic and simple and straightforward." I thought, oh my God, what am I going to do? I was really proud of the album. I knew it was a great piece of work. I really believed in it, and so did all the guys that played on it. Then my deal with Atlantic sort of blew up in my face, because Jerry Wexler kind of went through his change of life and divorced his wife of 25 years and married his 27-year-old secretary. The typical scenario. I didn't want to go back to working at the health department, and so I just gathered up my carpenter tools and went to work as a carpenter.

NW: But you wound up getting a deal with Capitol eventually, right?

I did that for a couple of years. One day, Audie Ashworth, who was a producer here and also managed J.J. Cale, told me that Frank Jones — the head of Capitol's country division — was moving back here from Los Angeles, and needed some work done on his before he moved into it. In the meantime, I had pressed up a thousand copies of that first album on my own on the Torreón label. One day Frank came by while my friend Jerry and I were working on his house, and Jerry said to him, "Frank, you should hear Jim's record. It's really fantastic." Frank being a very polite Canadian said, "I'd love to." He loved the album, and once he got settled in his new office, he called me in to talk about it. I wanted to make a deal that was so attractive to him that he couldn't pass it up — didn't want him to have any risk in case it was a flop or something. Frank said, "How much do you want for the album?" I said, "Well, Frank, it'll take me $5,000 to pay all the musicians that played on the album." So I sold the album to Frank for $5,000.

The head of sales at Capitol said, "How can this be any good? We didn't pay anything for it." But the reviews started coming in and Peter Guralnick and Greil Marcus and all of the big time rock critics were just raving about it. But from the record company standpoint, it wasn't about the art, it was about the merchandise. I've always swum against the current, because for me, it's always been about the art, it's never been about the commerce. I think that's how great things are made.

Capitol picked up Talley's second, third and fourth albums; the fourth received so little promotion, though, that he decided to sign with Guy Clark and Jerry Jeff Walker's manager Michael Brovsky, who advised him to leave Capitol and in fact told them Talley would be leaving the label on his behalf.

JT: Mort Cooperman, who owned the Lone Star Café in New York, took me over to the Empire Diner there on 10th Avenue. He says, "I got a call from Michael Brovsky and he said he doesn't have time for you, and he wants me to take over your management." Well, I really didn't have any choice. I didn't know many people in the business. The business part of this is beyond your control. You have to depend on other people, and if the other people don't come through for you, you're just hung out to dry.

Talley still lives in Nashville, and just turned 82.

JT: Only the sky and the mountains live forever, as the Native Americans say. You get to a certain age and it's a full-time job taking care of your health. But I'm still writing and, you know, I still got the calluses on my fingers. I can play, and I love playing my songs for people.

NW: To go back to Got No Bread, No Milk, No Money, what was it like having [legendary fiddler] Johnny Gimble on the album, since he worked with Bob Wills and the album was so inspired by Bob Wills?

JT: I was looking for a fiddler to play on the album because I really needed that fiddle sound. My bass player said we should get Johnny Gimble. I didn't know who Johnny Gimble was at the time. He told me that he had played with Bob Wills and I said, "Well, hell, if he played with Bob Wills, let's try to get him." Johnny agreed to come in like all the rest of them and play on spec and it just just blew us away. I've never seen any musician before or since who could capture a song so quickly, and come up with something so intuitive, so fast. He really was incredible.

I think Johnny was around 53 at the time we recorded that album if I'm recalling correctly, but he was just as gracious as could be and he told the most wonderful stories. We were recording my song, "Are They Gonna Make Us Outlaws Again?" [on his second album], and I said to Johnny, "Do you hear a fiddle part on this song?" He said, "James, you're asking the wrong guy. I never heard a song yet that I didn't hear a fiddle part on."

Those guys like him and Josh Graves and B.B. King, those guys that picked cotton and came up the hard way back in the old days, they had so much soul. They really did. I just feel so grateful that I was able to be around them and play with them.

NW: How did your family react to you doing an album about your Oklahoma roots and to them?

JT: I think my Aunt Ruth was quite excited about it. My mother was kind of stoic. She always wanted me to be a school teacher, never thought there was a whole lot to this music business thing. She never came to a single one of my performances. They came up the hardest on a dirt farm in Oklahoma, and she worked her ass off to get through Oklahoma State University in the late thirties and early forties. She was a very stern, dedicated, hard woman, really. I know she loved me and I loved her, but she didn't put up with any foolishness, I'll tell you. And of course, my father was dead. Now, my mother said many times, "I wish your father would have been able to hear this. He would have been so proud."

NW: Putting the album together, what was most important to you as you were trying to commit those songs to record? What were you thinking about aesthetically?

JT: I wanted them to be honest. I wanted them to say what they had to say and I wanted it to mean something. I was not thinking commercial at all. It was all about the art and music. Every publisher I went to when I was young here in Nashville wanted to try to turn me into one of these Nashville commercial songwriters. But I always saw myself as an artist, probably the same as Guy Clark — we were artists. It was the same as an artist who paints a painting or someone who writes a novel or writes poetry or something. I think that's the reason in my case that I never co-wrote with anybody. Carl Sandburg didn't co-write his poetry. John Steinbeck didn't co-write his novels. If you're an artist and you have something to say, you have something to say. I've never understood this Nashville thing of setting an appointment for 10 o'clock or two o'clock and two or three people getting together and trying to hammer out a song.

Those songs were honest, and the notes that were played on them were honest. You couldn't get anybody any more honest than Johnny Gimble. He told me when I was doing my fourth album, "I did that album for CBS, Fiddlin' Around. They want me to do another album. But they just want me to play standards and play the melody line with my fiddle — but that's not fiddling to me." He had so much integrity. He was an artist, too.

NW: Given that you felt like an outsider in Nashville, did you feel of a piece at all with the "outlaw" thing that was happening around that time?

JT: I never felt part of that outlaw movement. That was a bunch of bullshit. I mean, it was a marketing gimmick. When I wrote, "Are They Gonna Make Us Outlaws Again?", I was writing about real things. Writing about the American people and what they were going through. On my last album, I wrote that song, "Jesus Wasn't A Capitalist." There's not a dishonest word in that song. To me, that's what's important, I've always tried to write something meaningful, you know, that chronicles something about American people and American life. The same as John Prine did. John Prine was an artist and a dear friend as well. I talked to Mickey Newbury just a few months before he died. I never could understand why Mickey wasn't the star instead of Kris Kristofferson, because Mickey was such an incredible writer — not that Kris wasn't. But I mean, Mickey Newbury was just a phenomenal songwriter. "James," he says, "what you don't understand is we can't make a living off of my songs. If it wasn't for my wife's teaching salary, we couldn't live." And I was just flabbergasted — how can someone write all those absolutely beautiful songs and still have to depend on his wife's teaching salary?

Guy Clark said you can either come to Nashville and try to be a star and play the game, or you can come to Nashville and try to be a poet. Obviously that's what he tried to do. That's what I tried to do. That's what John Prine tried to do. I mean George Jones' song, "He Stopped Loving Her Today," that was written by two people; Willie Nelson's "Always On My Mind" was written by three people. So every now and then something really beautiful falls through the cracks. So I'm not saying anything derogatory against that approach, it just wasn't the approach for me. And I just have this feeling that real art will last for a long time.